by Rich Moreland, July 2016

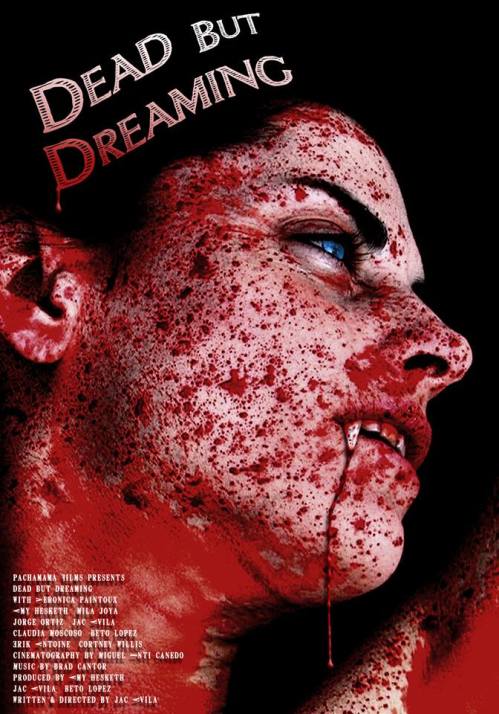

Olalla is an erotic horror film from Pachamama Films and Decadent Cinema. The movie is written and directed by Amy Hesketh. The dialogue is a combination Spanish and English and comes with the option of closed captioning.

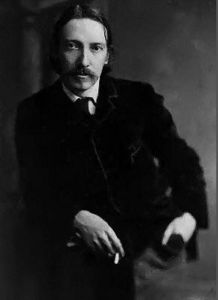

Based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s short story by the same name, Amy’s adaptation weaves Stevenson’s tale into a visual narrative so compelling that I believe it is worthy of academic study.

Though I don’t use a rating system for my reviews, I highly recommend Olalla. The film is available from Vermeerworks and Amazon.

In this first post, we look at Olalla from a back story perspective.

* * *

Robert Louis Stevenson published “Olalla” as a short story in 1885. It’s the first person account of an unnamed English officer wounded in war, most likely Napoleon’s 1807-1814 Peninsular Campaign in Spain. The soldier recuperates at a “residencia” belonging to a once noble family.

Robert Louis Stevenson published “Olalla” as a short story in 1885. It’s the first person account of an unnamed English officer wounded in war, most likely Napoleon’s 1807-1814 Peninsular Campaign in Spain. The soldier recuperates at a “residencia” belonging to a once noble family.

Remnants

When he arrives, the officer learns the remnants of the family consist of a mother who is “sunk in sloth and pleasure,” a “very cunning, very loutish” son named Felipe, and a daughter, Olalla, whose presence is felt but not seen.

Upon first encountering Felipe, the soldier finds him to be “a child in intellect [and] stunted in development.” He also describes him as secretive, perhaps being more than he seems. All the while, the daughter remains a mystery.

During his stay, the Englishman notices a portrait of a woman in his bedroom. She appears, by way of her antiquated dress, to be “long since dead.” Nevertheless, she is striking in an ominous way, causing the soldier to remark that “to love such a woman were to seal one’s own sentence of degeneration.”

As time passes, the portrait begins to “cast a dark shadow” on him. He is thankful the woman is “safe in the grave,” then comments, “And yet I had a half-lingering terror that she might not be dead after all, but re-risen in the body of some descendant.”

Reacting to his uneasy feelings, the officer concludes the ‘family blood’ seemed to be “impoverished,” probably from inbreeding, and accounted for the strangeness of Felipe and his mother.

How they are connected to the portrait remains vague, but the soldier’s lengthening stay at the residencia reinforces his growing anxieties.

Bestial Cries

The Englishman eventually meets Olalla and they develop a rudimentary friendship.

The story’s turning point occurs when the soldier cuts his hand opening a casement window. Seeking help he approaches the mother only to have her fall upon him and bite his hand “to the bone.” He fights her off but she pounces again “with bestial cries” similar to those that had previously awakened him in the night. Felipe and Olalla appear and rescue him.

With the Felipe’s assistance, the soldier departs the home to find shelter in a local village. While there, he engages the old padre and asks about Olalla and her family. Not a good idea, apparently, because the village atmosphere becomes toxic for the Englishman. The residents avoid his presence which he attributes to their superstitions. Eventually, he strikes up a conversation with a “gaunt peasant” and learns that a villager died at that “house of Satan” where the family lives, though how and why is unknown. The soldier dismisses the story as more superstition.

The officer and Olalla meet a final time on a pathway that has a crucifix at its summit. Olalla has stopped to pray.

She thought he had gone, she says, and urges him to do so because the longer he stays the closer death stalks him and her family. Olalla knows the locals are aware of his love for her and that is dangerous.

When her prayers are finished, Olalla implores the Englishman to look up at the “Man of Sorrows.” She mentions the “inheritors of sin” and how everyone must endure a past “which is not ours.”

Though he is no Christian, the soldier is struck by her message. All sacrifice is “voluntary,” he laments, and “pain is the choice of the magnanimous,” so it’s “best to suffer all things and do well.”

Moving on, the Englishman heads “down the mountain in silence.” He turns to look back and sees Olalla “still leaning on the crucifix.”

Is this a Vampire Tale?

Victorians loved enigmatic storytelling because it protected sensibilities and forced uncertainty upon the reader. For example, there’s Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. Is it a ghost story about possessed children or just the fertile imagination of a young governess who is a psychological wreck?

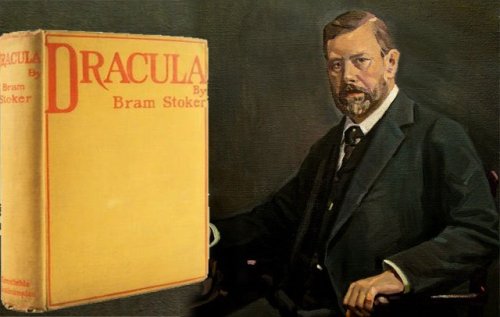

On the other hand, when Bram Stoker’s Dracula is published about the same time as James’ work (1897-98) subtleties are put aside. The vague becomes obvious.

We know Dracula’s bites are metaphors for the erotic and necessary to accommodate Victorian temperament, but the rest is pretty straightforward, a fantasy complete with fangs, a sun phobia, no reflections in mirrors, and on and on.

Hollywood has made a fortune on the Stoker model.

With Stevenson’s “Olalla,” we are left with a burning question? Is this a vampire tale or just a story about a deviant family of blood fetishists mixed with religious overtones and village superstition? Challenging, of course, because none of the standard Stoker’s mechanisms are in place and rightly so since Stevenson’s narrative predates Stoker by over a decade.

My inclination is go with the fetish explanation because everybody’s got one of some sort or another. But, of course, that won’t keep you up all night ready to cringe at the least gust of cold wind or that strange creature crawling up the wall of your bedroom.

As for Amy Hesketh’s adaptation of Stevenson’s Victorian imagination, well, it’s pure Amy which means it’s innovative and terrific.

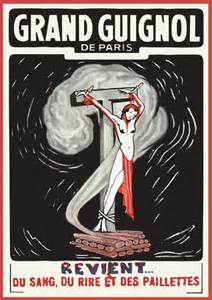

One more thought, I’m guessing Amy is a fan of Paris’ Theater of Horror, the Grand-Guignol (1897-1962), where amorality, brutality, sex, and insanity crept onto the French stage with just the right infusion of gore. No supernatural here, it’s all realism at work.

As Amy Hesketh fans know well, she relishes whippings, crucifixions, rack torture, and burnings too much to rely exclusively on the supernatural as her literary modus operandi. Realism is her performance art and what stands her tall in the crowd of horror directors and storytellers.

* * *

Having introduced Robert Louis Stevenson, we’re now ready for the next post on this marvelous film. We’ll take a look at the vampire question a little further.