by Rich Moreland, December 2016

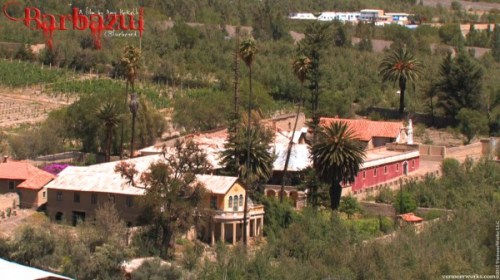

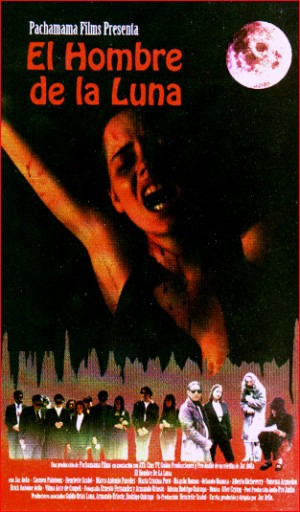

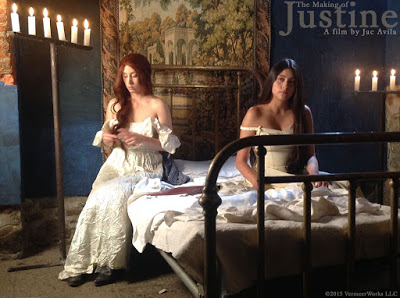

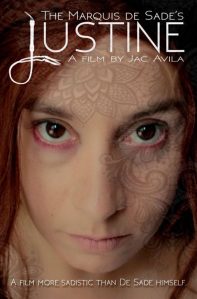

Now that we’ve discussed Justine, the novel, and looked at what Jac Avila has borrowed for his version of the story, we’re ready to analyze the film.

SPOILER ALERT! The ending of Justine is included in this five-part review.

All photos are courtesy of Pachamama Films/Decadent Cinema. Performer names are inserted where appropriate.

* * *

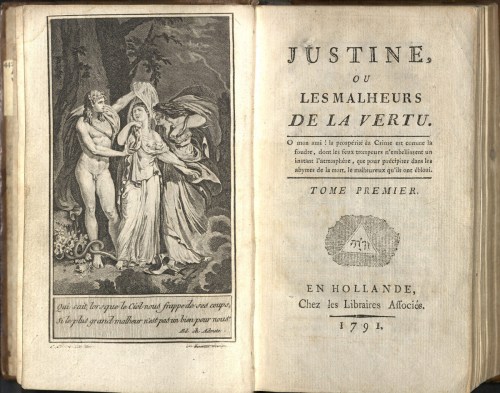

In a nod to the Marquis de Sade, Jac Avila’s cinematic version of Justine tells the story in flashback mode and sticks closely to the novel early on.

However, the opening scene departs from Sade and establishes that this film will forge its own path in ways that reveal Justine dabbling in the libertine philosophy she supposedly abhors.

However, the opening scene departs from Sade and establishes that this film will forge its own path in ways that reveal Justine dabbling in the libertine philosophy she supposedly abhors.

This is not to say Justine abandons her virtue, but the bottom line in this film is about defiance and empowerment that, contradictory to Sade, requires a woman of strength who endures her fate.

Jac Avila puts the abused lass on that trajectory.

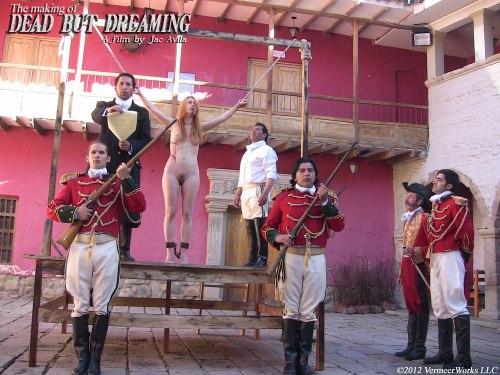

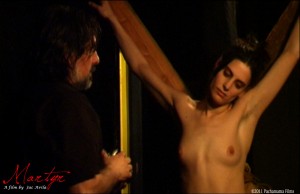

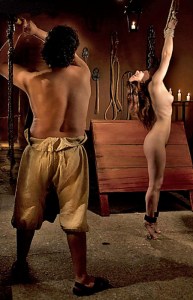

Public Humiliation

Justine (Amy Hesketh) is brought into the town square for a public scourging. It’s announced she’s charged with prostitution and theft and will spend a night in the pillory before being sent off to a “hard labor” fate.

Prostitution? Sade mentions nothing of that. What’s more, there is no public humiliation at the whipping post in his novel.

The officer in charge (Gonzolo Konka) isn’t finished because the crimes of murder and arson are also part of the charges. Justine escaped from prison with the gang leader Dubois (Gina Alcon) during a fire which our heroine supposedly set.

Twenty-one people died and later Justine is blamed for a second murder, that of Madame de Bressac.

So the unfortunate girl is doomed.

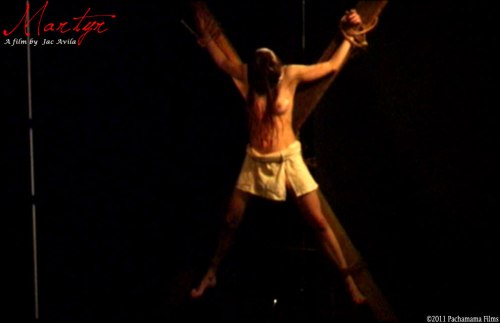

The flogging begins, the crowd counts the strokes, and Amy Hesketh initiates this provocative film in a fashion only she can orchestrate. It’s a superb scene and another cinematic triumph for an actress/director whose performance art we’ve come to take for granted.

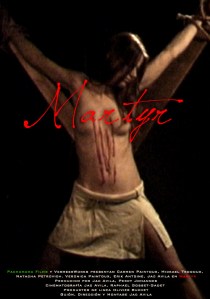

Notice the crucifixion position of Justine as a criminal. That’s important because this film has a religious undercurrent that challenges the Church.

By the way, after receiving the thirty-ninth lash, Justine faints and has to be revived. Keep in mind the number thirty-nine, it is significant in understanding the film and will be mentioned later.

The Medieval Church

That leads us to the prostitution charge. Why is it there?

It’s not part of Sade’s story, but its inclusion here makes sense if we remember that Sade is an atheist and condemns the Catholic Church as the charlatan of illusionary constructs. (See Justine, Part One: The Novel).

On the other hand, Jac Avila’s cinematic version of Justine does not abandon Christian ideology, choosing instead to confront it particularly over the Church’s attitude toward women.

Is the virtuous Justine turned into a modern version of Mary Magdalene, the supposed woman of the evening, to argue this point?

If so, the flogging scene with the priest standing by tells us two things that set the tone for the film.

First, doubts are cast on how we see Church doctrine when it comes to the female cause. After all, there is no real Biblical evidence that Mary Magdalene was an adulteress or profited from sex, though the patriarchal Medieval Church hinted otherwise.

Nevertheless, women were regarded as second class citizens, the Virgin Mary aside. She avoids what churchmen abhorred in the Early Middle Ages, the sensual woman. After all, she never really had sex.

Jac Avila challenges this minimalist view of the women in two other characters in the narrative, Rosalie (Mila Joya) and Omphale (Beatriz Rivera), who are present at Justine’s punishment.

Rosalie, Omphale, and Justine share the common bond of torture and pain, a point that becomes more important when the film delves into Rodin and his amusement with the fairer sex.

In fact, the girls are nervously watching a punishment that is already familiar to them.

That leads us to the film’s second theme: the empowered woman. Jac Avila’s Justine is hardly Sade’s innocent, hapless soul imploring Heaven’s Grace to save her.

She has her own will that leads to self-created problems . . . and she pays in the end.

But more on this feminist view later.

You Can Only Die Once

After her bloody punishment, Justine is taken to the pillory and secured to await the dawn.

The spectators are informed that by daybreak Justine’s execution will be settled upon since she has “but one life to live.” So much for the years of hard labor in the original sentence.

Juliette (Cortney Wills), a witness to the whipping, walks over and touches Justine’s cheek, asking how “you, with a very sweet face, find yourself in such a dreadful plight.”

A tearful Justine replies that were she to tell her story, she “would accuse the Hand of Heaven and I dare not.”

The dictates of her unwavering faith are understandable, though a bit over-the-top. But there’s more. Justine’s troubles are of her own making. Even for those who conceive of God as the great clock maker (popular with the Deists in Sade’s time), the miserable wretch has to bear some responsibility for her actions.

Sade would not disagree, but Jac Avila’s alternative look at an empowered Justine flies in the face of the French aristocrat.

Remember, empowerment means making choices.

Pounds of Flesh

The executioner (Eric Calancha) puts aside his whip and sodomizes his helpless victim.

Rodin (Jac Avila as actor) approaches Juliette and introduces himself. She responds with “Madame de Lorsange.”

By this time, the executioner has finished with his pound of flesh, so Rodin politely excuses himself to duck behind the stocks for his own Sadean go at Justine. Juliette looks on with patience, thoroughly amused.

In the face of all plausibility, Justine calmly begins as Rodin pumps away. Apparently anal violation at the hands of a pedophile sparks casual conversation. It’s a parody of Sade, of course, whose own narrative of Justine’s travails is so outré as to garner chuckles. But does Jac Avila also parody the Church in a way Sade ignores?

If that’s not enough grist for the mill, consider the film’s flashback narrators. Justine, and later Juliette, break the fourth wall and talk directly to the camera, engaging the audience directly with a more pointed method than a simple literary first person.

What’s going on here?

A lot, actually, and it sets up a very entertaining and highly recommended film.

In the next post we’ll find out the details of Dubois, Saint-Florent, and Bressac.

* * *

One of the endearing aspects of indie film is the cooperation that is built into everyone connected with the project. When money and time are limited, the cast accepts responsibilities to assist the director of cinematography.